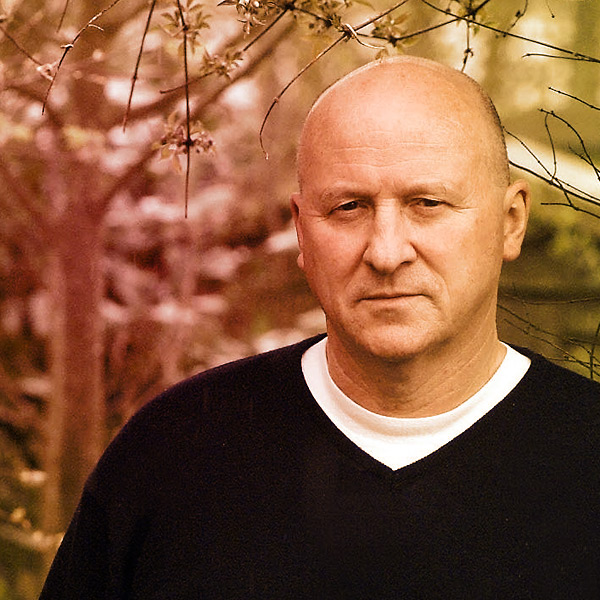

“The music of Gavin Bryars falls under no category. It is mongrel, full of sensuality and wit and is deeply moving. He is one of the few composers who can put slapstick and primal emotion alongside each other. He allows you to witness new wonders in the sounds around you by approaching them from a completely new angle. With a third ear maybe…” — Michael Ondaatje

Composed in 1969, The Sinking of the Titanic is Gavin Bryars’ first major work — a performative soundscape based on the musicians who played a hymn tune on the ship’s deck in the final moments of one of history’s deadliest maritime disasters.

While preparing a performance of Gavin Bryars’ The Sinking of the Titanic for the Suoni per il popolo Festival, Innovations en concert’s Isak Goldschneider spoke with the composer about the work’s genesis and core concepts.

Innovations en concert’s in-house ensemble Innovarumori will present The Sinking of the Titanic on June 11th at the Sala Rossa at 8 pm, in a program which also includes William Hesselink’s filmharmonic orchestra performing Popol Vuh’s score to Werner Herzog’s Nosferatu the Vampyre.

I understand that you wrote The Sinking of the Titanic in support of what you call “beleagured” students at Portsmouth [School of Art]. What was the story behind this?

Well, I was teaching (like a number of English experimental musicians at that time, people like Cardew, John White, and others) outside the mainstream of established music. We were not really employable in universities or music conservatories at all. But visual art cultures were very open to all kinds of ideas, and during the late sixties and early seventies they employed artists from outside the visual arts in their departments as a way of giving students access to other approaches and ways of making art. It worked both ways; those teachers experienced the way in which visual artists built their aesthetics and thinking, and saw what impact that could have on their own practice.

Now I was teaching in Portsmouth for quite a while, giving courses in the Fine Arts departments. The students who I worked, generally, with were those who were working in non-traditional media- they were interested in events, in performance, in video. This was roughly around the time of late Fluxus, and that was the kind of ethos at play. Those students who were working in that way were, to a certain extent, disparaged by some of the more conservative members of the Fine Arts department- very good craftsmen in terms of making brass sculpture or stonework, but who couldn’t see the point of what the others were doing. So these students’ work was being attacked and deemed not suitable for an art college environment, and they were being given a really hard time. They put on an exhibition of their work, and those members of the staff who were sympathetic to them were asked if they might care to contribute something. That’s where I contributed a page of typed script — a sketch — for The Sinking of the Titanic and what a piece about the sinking of the Titanic might actually be.

So it’s a piece born out of an conceptual exchange between disciplines?

Yes. And also from the fact that, at that time, aesthetic thinking in the visual arts was way ahead of what was going on in musical arts. I mean, I exclude Cage from this, but the mainstream of classical “contemporary” music was way behind in terms of the rigor of aesthetic questioning, the kind of curiosity and the possibilities available in the visual arts. I’m thinking, obviously, of things like Pop Art, conceptual art, landscape art, installations — these were outside anything that could be conceived by musicians. So the art people were always ahead.

Music seems to have a… well, if not conservative, then conservationally-oriented mode of thinking in music.

Look… I’ve moved onward to a certain extent in that I do believe that in becoming a composer you do have to develop craft. But you don’t have to develop craft at the expense of ideas. So when I’ve taught composition, I’ve never tried to impose anything on a student regarding the nature of their thinking. I’ve tried to develop their experience to help them do what they’re doing better and more effectively. I can make suggestions, but I’d never say “you should write like this” — in fact, quite the opposite. I’d try to discover what kinds of things a composition student was interested in doing. The question is then where these ideas come from. Often they come from other musics, or other sources of art, or even from outside art. And then it’s about how they bring those ideas into musical form — and to do that, you need to capture expression. I’ve frequently worked with musicians who don’t know how to read music, so they tell me what they’re trying to do and I write it down- that’s how I worked with Brian Eno. Quite often, some of those people would say that they don’t want to learn to write, that it might inhibit their thinking.

It’s curious how a tool as powerful as notation can limit the musical arena through its intentions.

I think that it can be quite intimidating- some people come into contact with a score and are amazed that someone can breathe life into these scribbles on paper. They can’t comprehend how that can be possible, while we know that it’s not hard at all.

I didn’t expect art students to be skilled or even able to perform musical notations- but in the end we performed pieces by LaMont Young and Christian Wolff, graphic scores by Cage, graphic scores by Feldman, all kinds of Fluxus works, where what’s interesting is that the concept is formed by the kind of ideas someone brings into a piece when they’re realizing it. That comes from their, if you like, aesthetic resources; and it seemed to me that the art students had masses of those while the music students had far fewer.

When I wrote The Sinking of the Titanic I was tapping into this idea of conceptual art; the idea that art is contained not in the glimpse of the art but in the ideas contained within it. That’s interested me a lot- that the appearance of the piece, its manifestation, is just a small aspect of itself. The main thing is: what are the ideas and concepts within it? Now with this piece- at the outset I thought that by actually researching the piece, by handling descriptions and notes and so on, I could make a kind of score and a person reading this would have a kind of performance in their head. And that would be the piece.

So for three years I didn’t make any live performances at all. I considered the piece to exist in this private, hermetic way. It was only three years later that someone challenged me, saying “Well, that’s great, but if someone else were to hear it, what would it sound like?” So then I had to make a realisation for the first time, to put it into a public space.

A process of conceptualization, provocation, and realisation.

I was also very interested in Cornelius Cardew’s graphic score Treatise, which is 190-odd pages of graphic notation. Someone at that time suggested that Treatise is like a map of a compositional mind. So you see the shapes and processes, but none of it is concrete; you’re not sure how to make it alive and real. It’s down to the individual to enter into this compositional cloud, and to extract something that does become real.

attend the Gavin Bryars concert

at Innovations en concert, Mon, 11 June 2012